-

- marketing agility

- Teams

- Organizations

- Education

- enterprise

- Articles

- Individuals

- Transformation

- Solution

- Leadership

- Getting Started

- business agility

- agile management

- going agile

- Frameworks

- agile mindset

- Agile Marketing Tools

- agile marketing journey

- organizational alignment

- Agile Marketers

- People

- Selection

- (Featured Posts)

- strategy

- agile journey

- Kanban

- Metrics and Data

- Resources

- Why Agile Marketing

- agile project management

- self-managing team

- Meetings

- Scrum

- agile adoption

- scaled agile marketing

- tactics

- scaled agile

- AI

- Agile Leadership

- Agile Meetings

- agile marketing training

- agile takeaways

- agile coach

- enterprise marketing agility

- Scrumban

- state of agile marketing

- team empowerment

- Intermediate

- agile marketing mindset

- agile marketing planning

- agile plan

- Individual

- Team

- Videos

- agile marketing

- agile transformation

- kanban board

- Agile Marketing Terms

- traditional marketing

- Agile Marketing Glossary

- FAQ

- agile marketing methodologies

- agile teams

- CoE

- Scrumban

- agile

- agile marketer

- agile marketing case study

- agile marketing coaching

- agile marketing leaders

- agile marketing metrics

- agile pilot

- agile sales

- agile team

- agile work breakdown

- cycle time

- employee satisfaction

- marketing value stream

- marketing-analytics

- remote teams

- sprints

- throughput

- work breakdown structure

- Agile Marketing Teams

- News

- agile brand

- agile marketing books

- agile marketing pilot

- agile marketing transformation

- agile review process

- agile team charter

- cost of delay

- hybrid framework

- pdca

- remote working

- scrum master

- stable agile teams

- stand ups

- startups

- team charter

- team morale

- user story

- value stream mapping

- visual workflow

There are two possible paths to releasing any marketing campaign into the world.

The first is the Big Bang approach, which treats marketing as a secret weapon that gets unleashed onto customers to generate a shockwave of response.

Except when it doesn’t.

But we’ll get into that in a moment.

The second is an experimental approach, which bases its structure on preliminary feedback from the customer before dedicating resources to any particular direction.

Marketers have a lot to gain from testing their assumptions through experimentation before going all-in on any given idea.

Which is why, in order to encourage marketing success, Agile ways of working support an iterative cycle of experimentation from ideation to execution.

Agile marketers can leverage concepts such as minimum viable campaigns, work breakdown structure, and metrics in order to disprove or prove the assumptions they generate internally and de-risk their next steps before the brands they promote can suffer the consequences.

In this article, we dive into each of the crucial steps that make Agile experimentation so powerful and explore how marketers can make use of them in their daily work to decrease the chance of failure and increase the chance of success of their marketing projects.

These same principles apply to marketing and to business agility more broadly. Even if you're operating in a highly regulated industry like BFSI or HLS, Agile experimentation can transform how you operate and give you a significant competitive advantage.

Minimum Viable Campaigns vs Big Bang Campaigns

What do Pepsi’s Live for Now, Nivea’s White is Purity, Monopoly for Millennials and the Peloton Christmas Ad from a few years ago have in common?

They’re all examples of expensive, Big Bang campaigns executed by the marketing teams and agencies of well-known brands.

They’re also all marketing campaigns that flopped and failed in front of the very customers they were trying to serve. In fact, in Peloton’s case, their inability to capture their audience’s reality translated into a $1.5B billion loss in market value overnight.

From the outside looking in, all of these campaigns appear to have been executed without the use of experimentation. Let’s examine the evidence.

Hallmarks of the Big Bang Marketing Campaign

For starters, a simple customer survey or focus group would have quickly shown that audiences just were NOT here for it. A small experiment would have resulted in the same audience reaction that customers experienced en masse when these campaigns were released globally all at once.

All Big Bang campaigns follow this familiar pattern.

A great idea is born internally inside the organization, it passes through levels of approval within the corporate hierarchy, and a project team is assigned to execute it.

When the team is done executing the preconceived plan, usually after many delays and lots of unplanned work, they release the campaign and all of its collateral to a target audience and hope for the best. In some cases, internal assumptions are proven correct and the campaign achieves desired results.

In many more cases however, Big Bang campaigns come-off tone deaf, forced, or just odd because they don’t reflect the customer’s perspective. They're so huge they upend the usual prioritization processes because everyone is just desperate to finally get it done.

Like a risky coin toss, Big Bang campaigns rarely manage to deliver on all of our customers’ expectations because, put simply, no one asked them in the first place.

Breaking down campaigns into smaller, low-risk experiments is the solution that Agile presents to this all-to-common marketing problem.

Agile Marketing Experiments and MVPs

Minimum viable campaigns unite two concepts that allow marketers to interact with customers before a big campaign launch without giving everything away in the process.

The MVP of a marketing campaign is“the smallest piece of marketing that successfully achieves its desired outcomes.” It represents the smallest subset of work we could release that still delivers value, but isn’t the whole complete piece of work.

A minimum viable campaign is also “the smallest thing our team could create or do to prove or disprove an assumption.”

With both of these good definitions of an MVP at the center of our work, we’re able to gather customer feedback to influence the final version of our marketing campaign.

As an additional benefit, MVPs also allow us to deliver incremental value to our customers much sooner than if they had to wait for the entire resource-heavy Big Bang campaign to arrive in their inbox, at their doorstep, or on their screen.

From both our internal marketing team’s perspective as well as that of our customer, delivering MVPs is a win-win approach.

Breaking Down Your Experiments

As an alternative to traditional Big Bang campaigns, large campaigns, like a new product launch, can be broken down into much smaller actionable steps that deliver value to customers sooner and with an increased rate of success.

To construct a viable experiment, the team must consider a number of different factors that make customer testing conclusive, factors such as:

- Is this experiment measurable enough to prove or disprove any of our internal hypotheses?

- Can the customer interact directly with this experiment reasonably?

- Can this experiment reach a wide enough audience to provide a conclusive sample of evidence that supports the hypothesis?

To construct a minimum experiment, the executing team must consider an array of other vital criteria, like:

- Does this experiment make use of the smallest amount of resources while still being viable?

- Does this experiment represent a part, not a whole, of the entire campaign we are envisioning?

- Is this experiment small enough that it can be built in a reasonable amount of time?

The perfect MVP lives at the intersection of what is minimum and what is viable, so marketing teams must account for both to construct an appropriate experiment.

What Happens After You Choose the MVP

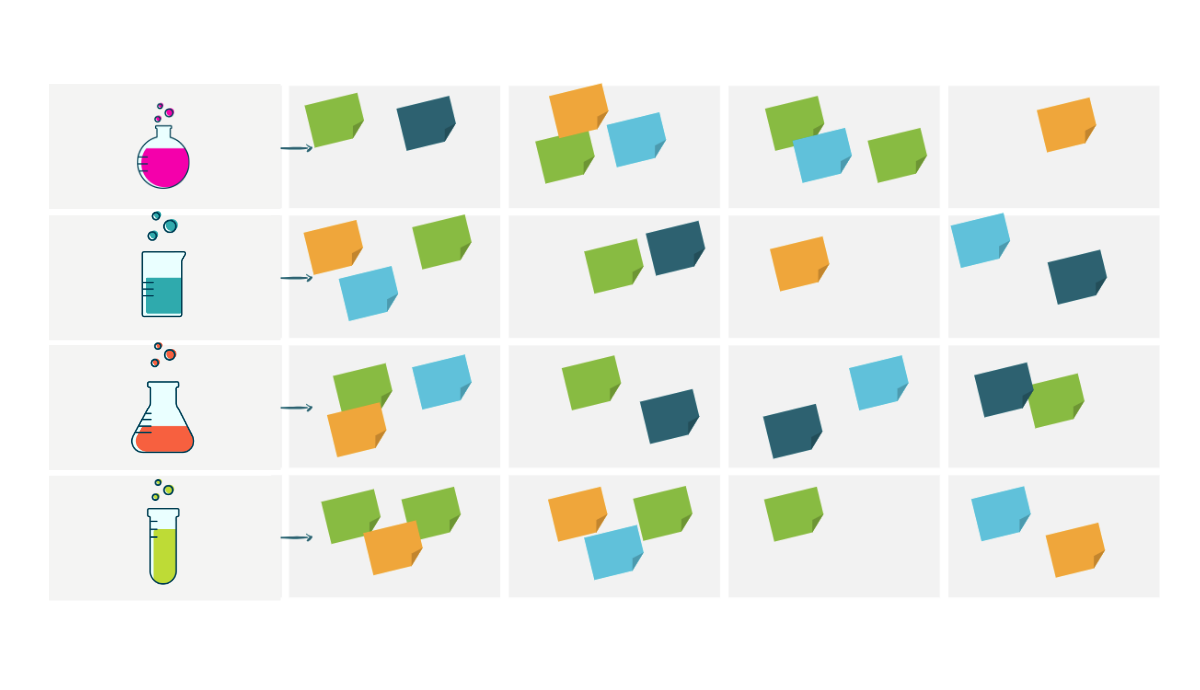

Once a series of minimum viable experiments has been defined, these can be mapped on a test roadmap which the team can use to stay on track. Agile teams will recognize this roadmap as the Pivot and Persevere diagram, as seen below.

The diagram’s name refers to the process teams use to move through their experiments and make decisions.

Based on the results of each experiment, the team can decide whether to pivot, meaning to change direction or tweak their initial assumption, or persevere and continue in the same direction and allocate greater and greater resources towards it, on the path towards a full-blown completed campaign.

Depending on the characteristics of the product, a pivot and persevere diagram for a new product launch may include any of the following experiments (and many more) to test proposed messaging, colors, design etc.:

- Customer focus group

- Customer survey delivered to an audience segment

- Blog post on company blog to query interest in a certain topic

- Social media campaign testing different visuals and their impact

- A/B test of different landing page on company website to identify high performers

- Webinar introducing a theme of the new product

- Series of testimonial videos emphasizing different angles of the new product

Like any work the execution team is doing, MVPs also find representation on the team’s visualized workflow (ex. Kanban board).

Experiments identified in the test roadmap will be broken down even further into granular tasks that can be tracked on the Kanban as the team makes progress on each MVP, from fleshing out the idea for the experiment to putting it out into the market and tracking how it performs in the wild.

Building Reliable Measurability Into Your Test

When it comes to MVPs, running experiments in the market is only one half of the testing process that high-performing Agile marketing teams must go through for best results.

In fact, the whole reason MVPs exist is so that they can be measured.

Without the right measurement tools and benchmarks in place, it can be very difficult to capture the data from all of our experiments and make data-driven decisions.

There are many aspects of customer interaction with our experiments that we want to measure, but there are really only four elements of our experiments that we can reliably measure using the digital marketing tools at our disposal. They are:

- The AMOUNT of activity on our site — page views, visitor sessions, returning visitors, etc.

- The SOURCE of that activity — referrers, search terms, languages, countries, organizations, etc.

- The NATURE of that activity — entry pages, exit pages, browsers, platforms, JavaScript versions, cookie support, screen resolutions, page refreshes, page load errors, average time per page, etc.

- The RESULTS of that activity — click trails, most requested pages, number of page views, sign-ups, orders, etc.

In order to gather the data that can help us make the right choice whether to pivot or persevere, our teams need to be certain that the following components are in place before the test goes out:

- Based on the experiment, a defined set of metrics that can prove or disprove our hypothesis reliably (ex. email opens or clicks for a campaign, registrants for a webinar, traffic that converts on a landing page). In this step, steer clear of vanity metrics like views or impressions. You’re looking for the members of your customer segment that have deliberately raised their hand for your offer.

- A way to measure the impact metrics that matter over the course of the entire experiment. Whether it’s a tool like Google Analytics, Hubspot, or a customer script on your website, you’ll need a system in place for capturing live customer data from your test.

- A benchmark based on historical data that can provide an indication of the test’s failure or success. For example, if we’re marketing a product with a high price, 10-15 interested customers might be enough to constitute a successful experiment. However, with a $1 mobile app, we might need the interested customers to be in the 1,000s to safely say that our experiment was a success. Depending on the type of campaign and the type of experiment, an appropriate benchmark will help teams understand whether their test was a win or a flop.

- A timeline for each experiment that is an appropriate amount of time to generate results. The team must decide whether a viable experiment of this nature will need to run for 2 weeks or 2 days in order to generate a reliable set of data.

It’s Not Iteration If You Only Do it Once

A large campaign borne of a single experiment is, in almost all cases, a Big Bang campaign. One experiment is simply not enough to gather the information we need.

A Big Bang campaign, in all its forms, is a dangerous mess of assumptions. In order to unravel and dissect its pieces and make an informed decision about what our customers want and need, we need to be prepared to put each of its parts to the test.

That is why, in order to reap the full benefits of iterative experiments, Agile marketing teams test a number of different assumptions that converge to bring their large marketing campaign to life.

Testing and measuring customer feedback to a campaign’s visuals, messaging, design and intent means you’ll need to run a series of experiments to prove or disprove each.

Only then can we confidently arrive at a version of our original idea that our customers truly believe in and support.

Topics discussed

Improve your Marketing Ops every week

Subscribe to our blog to get insights sent directly to your inbox.